The following is the sixth in a seven-part series. We hope you’ll enjoy.

Only a few places in America have the combination of cold winters, temperate summers, year-round humidity, and nutrient-rich soils that make New York’s north coast such a fertile environment. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Webster became one of the nation’s largest producers of apples and other tree fruits, with bounteous harvests much in demand throughout the region—and well beyond.

Long before fast railroads made it easy to transport this luscious crop across the country, however, apple growers looked for ways to ship apples out of New York without ruining the fruit. One of the solutions emerged from the kitchens of Webster residents: drying the apples.

“They would core, quarter, and string the slices on a line to dry,” wrote Lynn M. Barton, Joan E. Sassone, and Mary Hasek Grenier in their book Webster. “By about 1870, small quantities were dried in the sun for sale to stores and for domestic use.”

Dried apples did not spoil, and they took up less space than fresh apples did. It didn’t take long before one local family saw the potential for shipping dried apples all over America.

John W. Hallauer came to Webster with his parents in 1849 from Schaffhausen, Switzerland. As an adult in 1864, he bought a 160-acre farm on Webster Road, planted orchards, and soon began drying apples from the harvest. The Hallauers embraced a new method developed in Mansfield, Ohio, for drying fruit in large quantities, and soon grew their volume to more than ten bushels every day during the harvest season. The Lippy and Linn method, patented in 1864, used a drying oven equipped with its own heater. Other inventors created cabinets that could hold more fruit, and by the late nineteenth century, commercial evaporators turned a whole warehouse into a drying enterprise. A Webster native, Elam Hatch, received the credit for building the world’s first commercial tower evaporator in 1873.

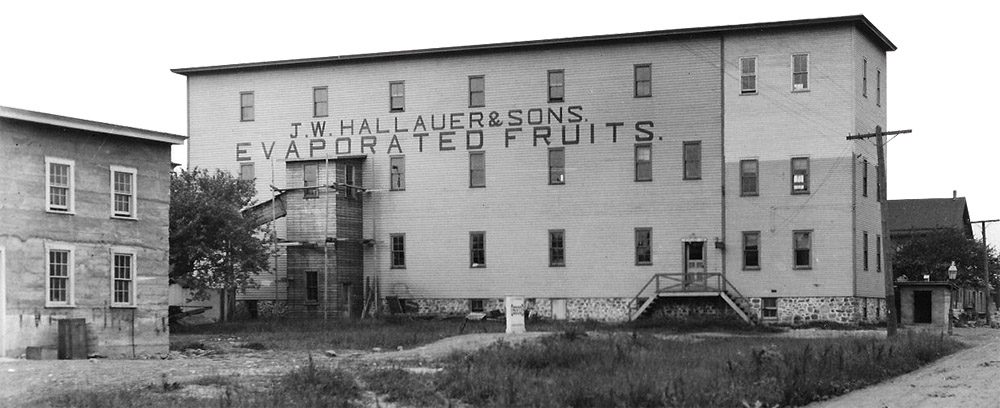

In 1890, J. W. Hallauer & Sons Evaporated Fruits opened a factory on North Avenue and began buying fruit from other growers. They shipped a large portion of their output to Hamburg, Germany, becoming one of the largest exporters in the world with drying factories in Missouri, Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, and West Virginia.

When John W. Hallauer passed away in 1909, his sons John J. and George inherited the business and enjoyed a life of unprecedented prosperity. But the ups and downs of the fruit market were governed by circumstances not always in their control. A single year of rough weather could cause a significant downturn in production. Worse, the kilns caught fire fairly easily, destroying an entire plant in the space of a

few hours.

Such a kiln fire in the Webster plant on December 6, 1904, left the company with “about eight thousand bushels of apples yet to dry,” the Democrat & Chronicle reported. This came barely a week after its plant in Nunda, NY, burned to the ground in the middle of the night.

Repeated disasters, a couple of bad crop years, and the resulting debt led Hallauer & Sons to declare bankruptcy twice: once in 1907, and again in 1913. World War I brought the Hallauers a bonanza in shipping dried fruit to feed the troops, but after the war, the Virginia plant burned down for the third time, and the banks refused to lead the business any more money to rebuild.

In 1926, George Hallauer moved his family to Yakima, Washington, where he established the Valley Evaporating Company and continued to see success in the fruit drying business. The town of Webster held its place in the fruit industry through World War II, until other kinds of manufacturing moved into the area, literally changing the landscape and transforming Webster for the long term.

Read the next piece in this seven-part series: Webster Canning & Preserving: Feeding the Troops & Nation